Rows: 228

Columns: 10

$ inst <dbl> 3, 3, 3, 5, 1, 12, 7, 11, 1, 7, 6, 16, 11, 21, 12, 1, 22, 16…

$ time <dbl> 306, 455, 1010, 210, 883, 1022, 310, 361, 218, 166, 170, 654…

$ status <dbl> 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, …

$ age <dbl> 74, 68, 56, 57, 60, 74, 68, 71, 53, 61, 57, 68, 68, 60, 57, …

$ sex <chr> "Male", "Male", "Male", "Male", "Male", "Male", "Female", "F…

$ ph.ecog <dbl> 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, NA, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1,…

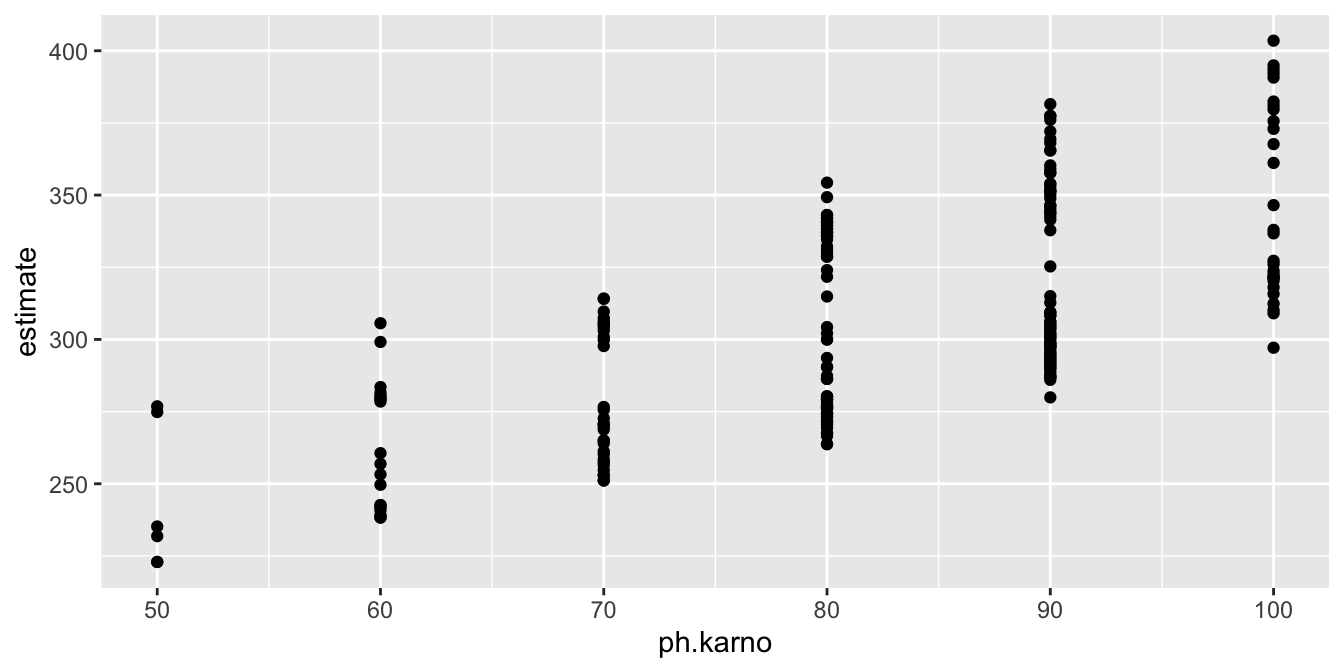

$ ph.karno <dbl> 90, 90, 90, 90, 100, 50, 70, 60, 70, 70, 80, 70, 90, 60, 80,…

$ pat.karno <dbl> 100, 90, 90, 60, 90, 80, 60, 80, 80, 70, 80, 70, 90, 70, 70,…

$ meal.cal <dbl> 1175, 1225, NA, 1150, NA, 513, 384, 538, 825, 271, 1025, NA,…

$ wt.loss <dbl> NA, 15, 15, 11, 0, 0, 10, 1, 16, 34, 27, 23, 5, 32, 60, 15, …